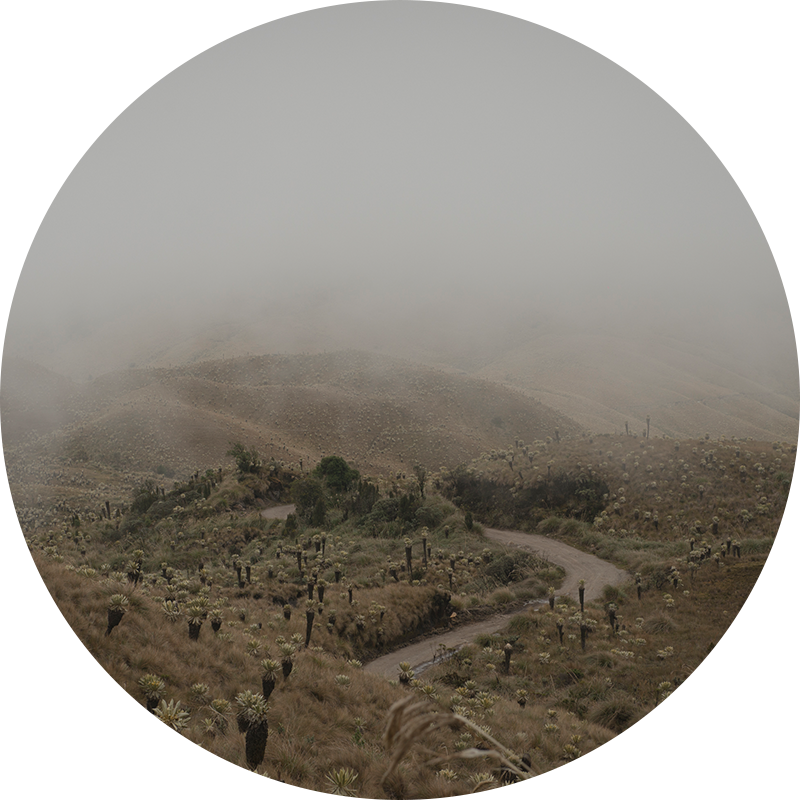

At more than 3,000 meters above sea level, amidst Andean moorlands, volcanoes and lagoons in the south of Colombia, live the Indigenous Pastos. The community divides itself into the three territories called resguardos, or safeguards: Panan, Chiles and Gran Cumbal. Other Pasto communities live across the border in Ecuador. “In spite of being divided by the border, our culture is present in both sides of the territory”, says Luis Aníbal Puenayan Naza with pride, the Autoridad Tradicional (Traditional Authority, a position of leadership within the community) of the Panan safeguard, and a cultural promoter and researcher of Pasto culture and society.

Shaucha Wuata is a project that seeks to preserve traditional agricultural techniques and five native varieties of potato in order to consolidate food security of the Indigenous Pasto communities of the Gran Cumbal region. It sponsors the development of three pilot centers, each with a native seed bank. The use of ancestral knowledge is encouraged, as is communal work that promotes reciprocity and gender equality.

The Indigenous Pasto communities are located more than 3,000 meters above sea level. Cold weather is predominant in Colombia’s western mountain range. The area is volcanic due to a significant number of orographic and coastal accidents. The region is characterized by a variety of thermal floors caused by its proximity to both the Pacific Ocean and the Andean peaks.